What will the cities of the future be like?

Projects for major events

14 February 2004

The cities of Socialism

5 June 2005by George Μ. Chatzistergiou

Forget tower blocks! The cities of the future are “shacks of recycled plastic and corrugated tin!”, notes an appalled Edwin Heathcote in his review of Mike Davis’s Planet of Slums in the Financial Times.

Often built on unstable ground or in dangerously polluted areas and with huge problems of water supply and sewage, slums do not lend themselves to cinematic extravaganzas. Films like the Brazilian City of God are the exception, and even then they are not representative of the situation. From an anthropological viewpoint, Luis Bunuel’s old film Los Olvidados comes closer to depicting life in such settlements. By contrast to the scant presence of slums in the cinema, they are frequently present in static photography. Even fashion magazines feature the occasional panoramic view of this type of habitation as an “interesting” phenomenon, or pictures of half-naked beautiful girls as proof of the beauty that may come out of squalor. In a similar vein, certain written accounts exalt the inventiveness of slum dwellers, forgetting that the human species is always resourceful when called upon to live in extreme conditions (“how is the action of slum gangs different from that of prison gangs?” asks a review that censures such idealizing approaches).

Amidst a host of references to slums –exhibitions (such as the 10th Biennale of Venice), books (many of which record the experiences of NGOs which are active in this field) and articles (from serious approaches to the low-taste, “Slums are In!”-way of presenting the ‘Cities of the World’, as the settlements of the poor of the 21st century are euphemistically called)– Davis’s book stands out and can serve as a valuable tool for going deeper into the matter. The author himself makes an extensive summary of the book in New Left Review (26, March-April 2004), recently published in Greek by Agra Publications.

Widely known as the author of books like Ecology of Fear and Dead Cities, Mike Davis is a special case of thinker who highlights in a groundbreaking way the dark sides of developments in general and cities in particular. The basis for this work was the historical report “The Challenge of Slums”, published by UN-Habitat in October 2003. To Davis, this report –the first truly global ‘audit’ of poverty in urban environments– is as valid a danger signal for global destruction as the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which represent an unprecedented scientific consensus as to the threat of global warming.

The metropolises of the poor

The poor of this planet are not only those in Asia, Africa and Latin America. One of the presidential candidates for the last US elections, Democrat Howard Dean, presented data about some 34 million people in the US living below the poverty line. According to the United Nations, over one billion people live in slums in the South. The collapse of agriculture and the so-called “structural adjustment” of the class stratification in urban centers are directly relevant to these developments. The strata of the traditional working class –with their regular employment and social security– and public servants are rapidly shrinking while the informal –and totally unprotected– sector of the economy is expanding dramatically. As summarized in the relevant UN reports, “instead of being a focus for growth and prosperity, the cities have become a dumping ground for a surplus population working in unskilled, unprotected and low-wage informal service industries and trade”.

Davis compares these developments with the catastrophic process which led to the creation of the Third World in the last phase of Victorian Great Britain (1870-1900), a reaction to which were the major agricultural revolutions of the 20th century in the form of national liberation movements; at the same time, he says that there is no historical precedent which would help assess the future developments in this explosively unstable world of the ‘new cities’: a “world little imagined by Mao or, for that matter, Le Corbusier”, as he notes. And while the external traits of this unparalleled retrogression to the living conditions of the age of Dickens and Oliver Twist resemble those in industrial-revolution Europe and America, it is actually a very different thing. With the exception of China –which is going through the largest industrial revolution in history– and perhaps parts of India, This explosion is happening in regions characterized by stagnation or ever negative economic indicators. This “twisted” development is connected with the policies of the International Monetary Fund from 1978 onwards, which contributed to ‘deruralization’ and the collapse of national economies.

Towards an alternative approach to the Greek ways of production?

If the approach to the slum phenomenon is crucial for understanding the overall trends in the course of human societies on a planetary scale, for Greece it may have a special relevance since an understanding of the mechanisms of evolution of such settlements could shed some unexpected new light on certain aspects of the building boom in postwar Greece.

This alternative view is linked with the theories of Hernando de Soto (whose book The Mystery of Capital was published in Greek by Roes Publications): the Peruvian economist and associate of the World Bank believes that slums are the modern equivalent of the poor districts in 19th-century London and Manchester and that, suitably handled (mainly through giving ownership deeds to slum dwellers), these settlements may function as paths towards mainstream capitalism and thence to prosperity. The ideas of de Soto are not new –even before World War II some North American economists claimed that the promotion of small-scale land ownership and entrepreneurship among populations under borderline conditions was the best antidote against both poverty and social unrest– but they are especially relevant in today’s Latin America, which is in constant social and political turmoil.

Davis sees the main hypotheses of de Soto’s theories as arbitrary because they correlate two entirely different situations: to him, the parallel of today’s slums is not London but Victorian Dublin, a unique phenomenon in the 19th century in that the destitution of its excessive population was not associated with developments in production but with the collapse of agriculture. In any case, there are major political obstacles to a general implementation of de Soto’s theories; in areas of the planet where the question of distribution and ownership of agricultural land remains unresolved, the large-scale concession of urban land titles would seem utopian.

Aside from the applicability of de Soto’s ideas in today’s Third (or Fourth?) World, his theory may have some relevance to postwar Greece. As an outpost of the First World, as a result of both geography and international politics, Greece developed a highly sophisticated “Building Exchange”. Concepts like antiparohi [the part-exchange of land for a portion of the building on it], the transfer of one plot’s coverage factor to another or the sale of a building’s ‘air’ [or future extension rights] make de Soto’s ideas look elementary. Nevertheless, his theory can help us systematize the hitherto disjointed approaches and arrive at a comprehensive interpretation of the “Greek method of production”, from the legalization of spontaneous urbanization (as Davis calls the profitable way of converting rural land into a peculiar urban one) to the overall building activity that characterizes a cheap way of development.

Multiplying borders

As the reserves of cheap land for slums dwindle all over the world, there is a rising phenomenon of heavily guarded ‘pockets of prosperity’ near or even within slums, where wealthy people live protected in ‘fortress settlements’ among potentially hostile populations. Davis describes some typical examples of this –in India, for instance– where life is organized as in American suburbs and even the names of streets, districts and malls reference California or New York.

In an age of diminishing importance of national borders, it is interesting that the phenomena of the entrenchment of population groups, far from decreasing (as a fair critic of the structures of nation-states would expect), multiply and intensify, they appear on a small as well as a large scale and, being directly associated with social inequality, undermine the operation of a democratic society based on the principles of humanitarianism and the Enlightenment.

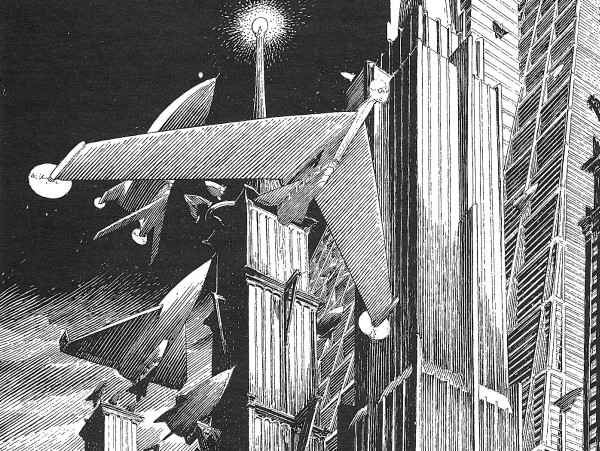

In his interesting sci-fi novel Cities in Flight, James Blish explores a future for humanity based on two critical inventions: antigravity devices that allow whole cities to abandon the Earth like giant spaceships, and anti-death drugs that enable their people to live for thousands of years. As the Earth falls into poverty, epidemics, environmental problems and stagnation, one by one the prosperous and orderly cities leave for the stars and thus promote the establishment of a unique Galactic empire…

Even if this is the definition of Heaven, we must still bear in mind the theologians’ warning: “before we can enter it we must undergo the judgment of the Second Presence”. In other words, even assuming that such a future could be attained by technological miracles and would be socially viable and desirable to some, how can the more speculative among us be sure that there will be a place for them and their children in such a city?