Projects for major events

My East End. Memories of Life in Cockney London

5 October 2003

What will the cities of the future be like?

14 April 2004by George Μ. Chatzistergiou

In 1893, just three years before the first modern Olympic Games in Athens, Chicago organized the World’s Exposition to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the New Continent’s discovery by Columbus. Another four years before that, in 1889, the Champs de Mars in Paris had hosted the famous Exposition Universelle – a magnificent international exposition for those times. The common characteristic of these novel events of the late 19th century –to which we must add also the first Great Exhibition of London in 1861– was their international scope. The display of products or activities had to do with people or objects from many parts of the earth, while among the aims of each event was clearly the desire to promote the organizing city and country on the international scene. Of course, the visitors to these events could not be really ‘international’, given the difficulties of traveling in those days; nevertheless, the already significant progress in transport (the railway, for instance) had facilitated traveling so much that these events had a markedly supra-local character. This scale of mass attendance to recreational events had not been seen since the days of the Roman Empire; and. As in those distant times, infrastructure and the special construction projects were central to these 19th-century exhibitions. In his book The Devil in the White City, Erik Larson, the award-winning journalist of Time magazine, starts from these technical projects and their process of execution to highlight the Exposition of Chicago, which is all but forgotten but no less interesting today; and he does it in such a lively way that his book topped the bestseller list of the New York Times.

National Pride

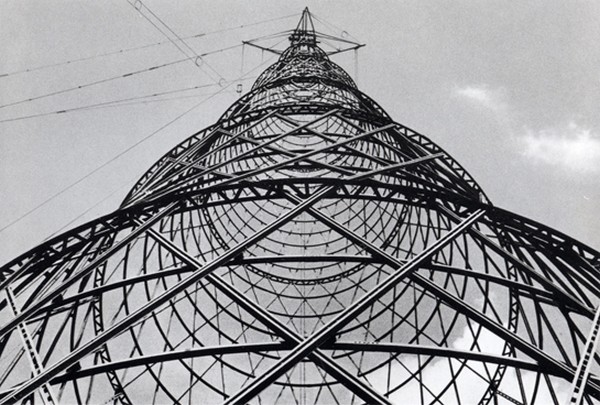

Aside from the general interest this book may have, its Greek readers may be helped in sorting out their experiences from the Olympic Games of 2004 in Athens. First of all, the entire book is permeated by the dramatic feeling that preparations were “behind schedule”, and there was a serious possibility that the Exposition would not take place. Characteristically, the architect Daniel Burnham who was in charge of the undertaking (and in whose office the inscription “Rush!” loomed large) was hard put to persuade the greatest figures in American architecture to become involved, as they feared that their reputation would suffer if the whole thing went wrong. After all, the aim was for the Chicago Exposition to have some buildings designed to exacting specifications (with very large openings, for instance) and, most importantly, a central emblematic structure which would ‘surpass’ the Eiffel Tower of the Parisian show. Indeed, according to Erik Larson things were complicated when Eiffel himself wrote to the organizers and offered to design such a structure for Chicago. In the end, ‘national pride’ prevailed and the solution they adopted was of American origin: the emblem of the Exposition was a huge, revolving metal wheel equipped with cars in which visitors could ride and admire a panoramic view of the city.

Erik Larson employs his journalistic skill to ‘report’ on a series of incidents which he connects as in a novel and thus narrates the superhuman effort behind the realization of the Chicago Exposition. At some point the famous L H Sullivan –a builder of skyscrapers in Chicago and of the designers of the buildings in the Exposition– fires from his practice the young architect Frank Lloyd Wright for engaging in his own private projects! On another page, the civil engineer who had designed the special metal structure writes a letter to the organizers in which he made the alarming statement that the finished blueprints were wrong because he had not calculated the wind loads properly! Elsewhere, the author describes how distinguished designers –such as F L Olmsted, the pioneer landscape architect and designer of the Central Park in Manhattan– were driven to nervous breakdown by their participation in this intensive process, or the many grave accidents during the construction of the buildings; indeed, it was said at the time that it was safer to work in a mine! He also relates the serious failures of some structures during the preparation, when roofs or entire buildings collapsed under windstorms or heavy snowfall, as well as the creative process which resulted in all buildings having the same color, so that the Exposition complex became known as the “White City”…

The author has carried out an admirable research in libraries and archives as well as in situ, where he stayed for quite a long time. It is true that a demanding reader would have expected Larson to go deeper into the technology of construction, and the absence of this is noticeable in the book. Nevertheless, Larson’s work is on a par with other worthy books on similar subjects, and it does provide an overall picture of the technical works by focusing on the process of conception and implementation instead of the usual presentation of the finished structures. In any case, Erik Larson goes beyond the technical projects to highlight the aspect of entertainment and the figures associated with it; a typical example is Buffalo Bill, creator of the Wild West Show, who came out of the Chicago event a very rich man but spent his fortune at such a pace that he died in poverty a few years later. At the same time the author unfolds a sinister side of the affair through the “diabolical figure” of Holmes, a psychopath killer who posed as a doctor and sought his victims –young and beautiful women– among the huge crowds who flocked into town to see the Exposition. Assuming that this aspect –which refers to a perfectly true story, anyway– was not inserted to boost the commercial appeal of the book, it can be said that the author attempts to round off his approach by pointing to the potential side effects from collective activities of such intensity.

Conclusions

After the end of the Exposition, and given that it had been conceived as an ephemeral project (“instant city”), the buildings were left to crumble and decay. The author closes the book with some conclusions. As he describes Chicago plunging into economic crisis after this highly successful Exposition, he suggests that the success of such an undertaking, if it is not an exception to the usual pattern, is at best the culmination of the way in which things operate for a whole phase, and at any rate it does not necessarily guarantee that things will be getting steadily better! On the other hand, Larson points out that after the “White City” experience large parts of the population realized that cities are not just places were people move in order to “make money”; in this sense, the Exposition promoted a change in people’s perceptions of the aesthetic of American cities and boosted the citizens’ tendency “to identify themselves with the achievements of their city” (civic pride). These conclusions may be of primary interest to Greek readers, even if we know that “history does not repeat itself”.

Erik Larson

The Devil in the White City

Bantam Books, pp440